Krzysztof Grzybacz in conversation with Helena Czernecka

Dawid Radziszewski Gallery

Clay.Warsaw, ul.Burdzińskiego 5

Warsaw Gallery Weekend 2022

Helena Czernecka: How do you know when a picture is finished?

Krzysztof Grzybacz: I have a system where I only work on wet oil paint, and when the paint dries, the picture has to be finished. It’s a kind of technical limitation that takes from one to three days, depending on the color—some colors dry in a single day and then I have to hurry to get the whole thing done. Sometimes it happens that the picture is finished because of the paint, but I’m not satisfied with it, so I either start all over, or I know it’s pointless and I give up, I just abandon it.

You told me recently that you’ve tried out various techniques, but in the end you stuck to the old method.

I recently mixed things up a bit—I put aside my box of toys I so adore and I tried something different. But it soon turned out that I was unconsciously trying to create my favorite, tried-and-true sculpted effect, which makes an oil painting look like it was done with acrylics. I tried to do that with another technique, one that was not at all suited for it. I wasted eight canvases making pictures that are unshowable. I was shattered, and the exhibition was getting closer… So I went back to my old method and that gave me a huge amount of pleasure, I understood I was in the right place and that did not keep me from further developing.

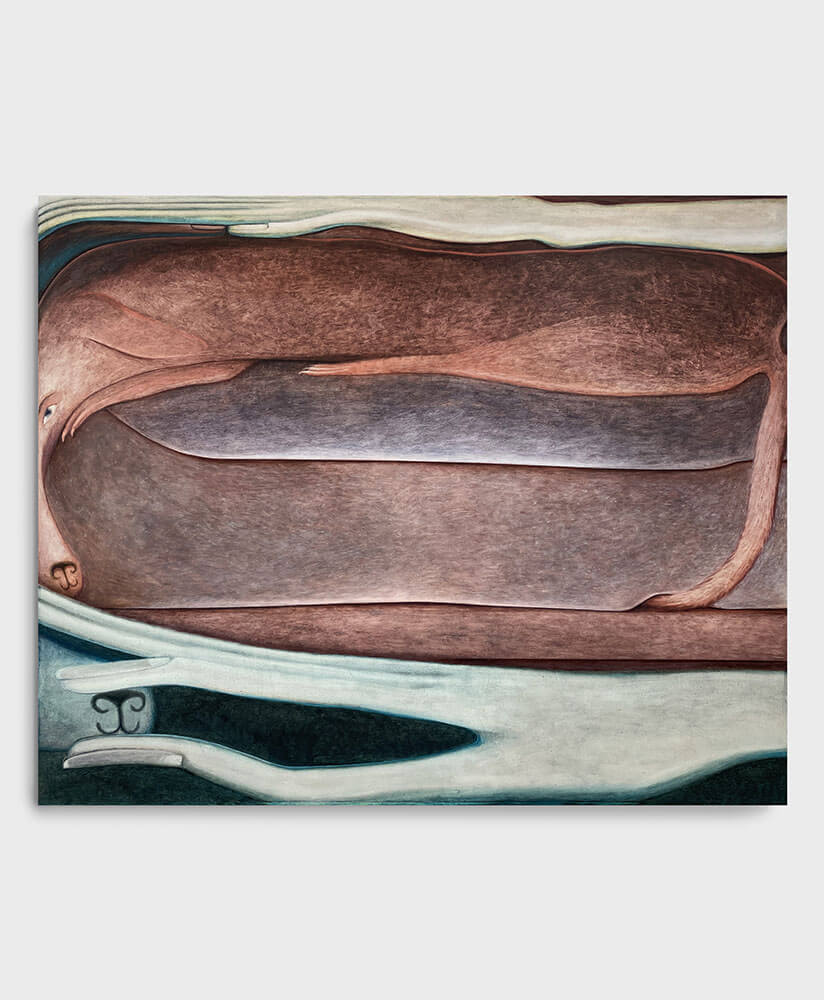

So the surface of your pictures is so thin because you only work on wet paint, and there are not so many layers.

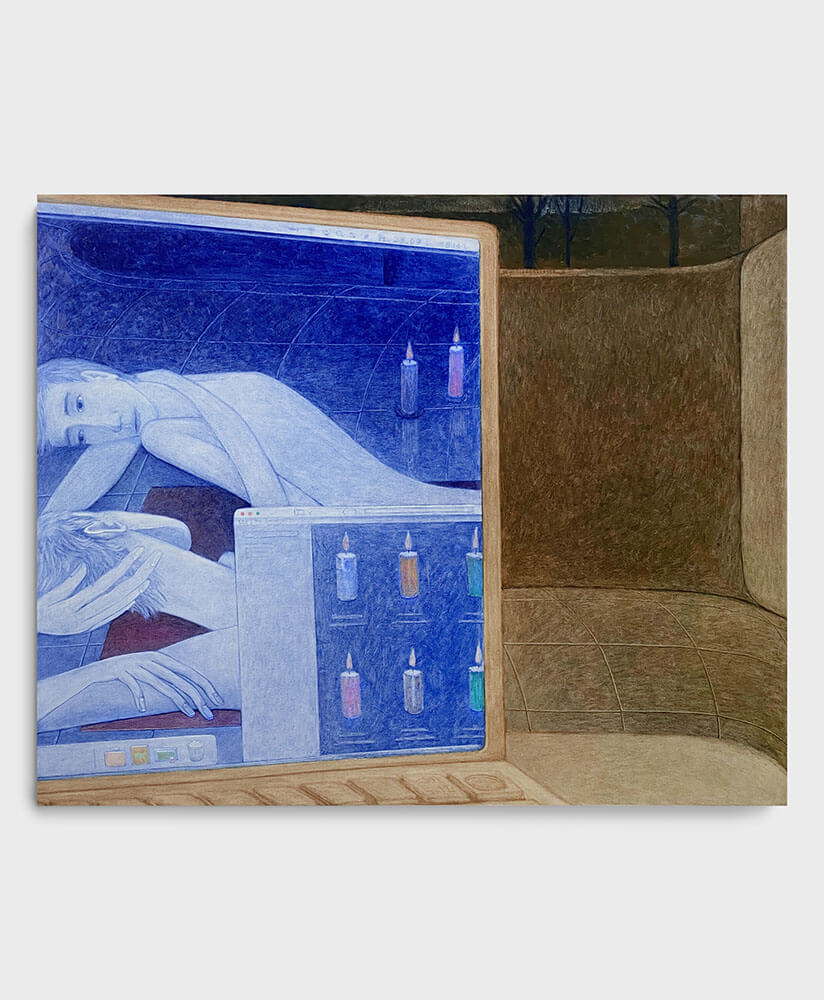

There are no layers at all. The technique is that the canvas is initially covered in one color of paint. Where there’s more paint, it’s darker, where there’s less paint it’s lighter. Instead of adding paint, I remove it. Of course, I add various things later, but the main movement is removal, mopping up. The best thing is a dish-washing or bath sponge. I’ve cleaned up for your visit today, but normally my apartment is full of sponges.

Do you have a clear vision of what you’re going to paint, or do you work spontaneously?

The first step is drawings. I make whole piles of them, this comes easily to me and helps me work out my ideas. I make these precise sketches of pictures, but it sometimes turns out that what looks good on paper is useless on canvas. Then the work starts from scratch. Due to the fact that I’m constantly coming up with various ideas and visions, I’ve become quite good at imagining things for future pictures and gathering up ideas.

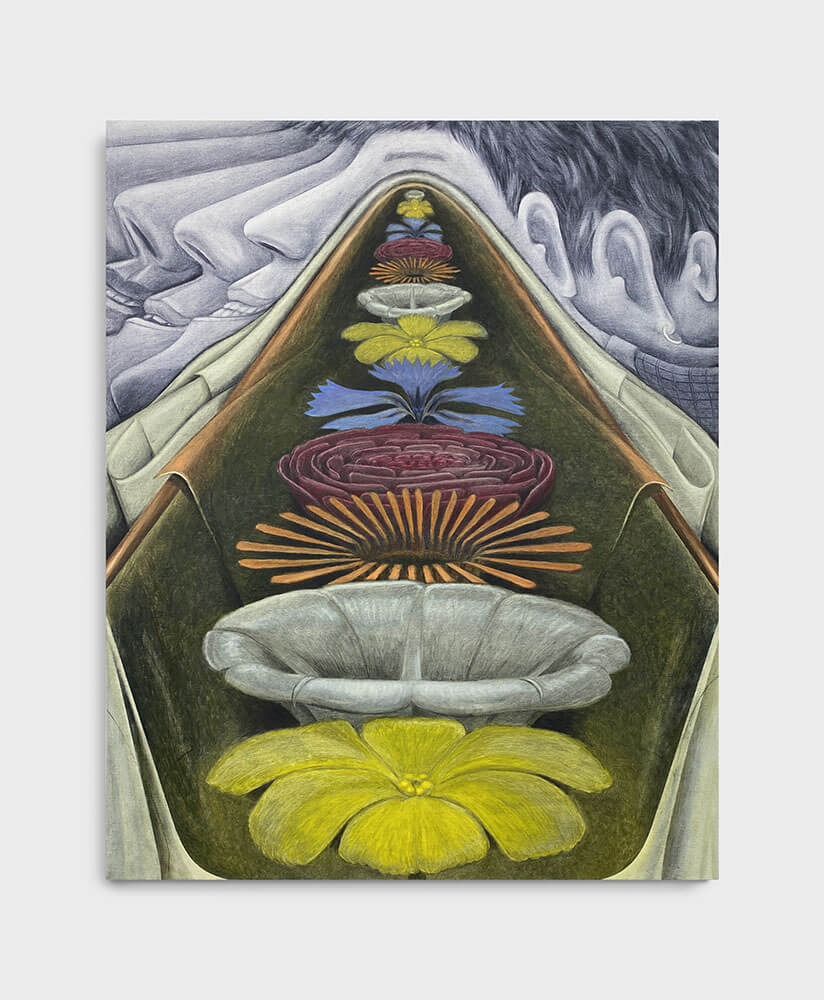

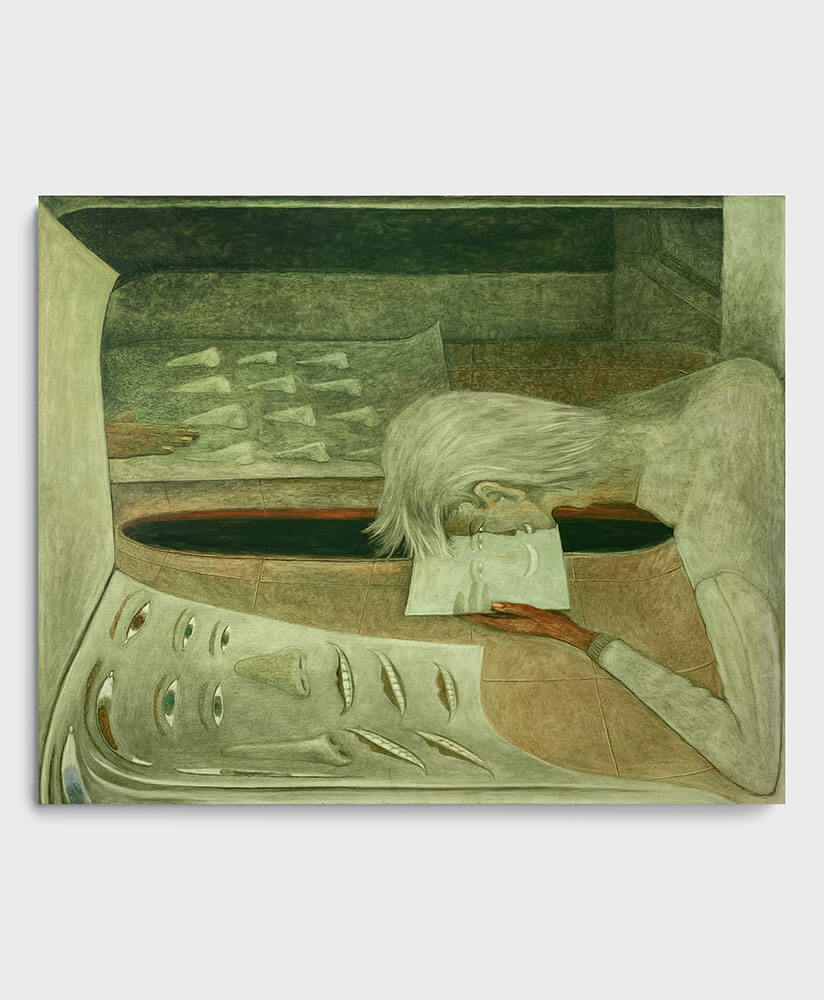

In your previous works the main protagonists were usually various everyday objects—nail clippers, make-up kits, perfume bottles… Now I see a fantastical figure in your pictures, one who studies himself in the mirror, he has noses, mouths, and eyes waiting on sheets of paper to one side. How does this scene relate to everyday life?

It came out of an hours-long drawing session. When I arrived at the studio the next day I decided that figure was kind of me, hunched over drawings for the past six months and inventing things to be illustrated; it’s a figure who makes a record of himself.

At what point in your life did you begin painting or know that you wanted to paint? Where did it come from?

I was brought up in the countryside, I’m also homosexual, and so I got the feeling I was like a mermaid in that environment. Instead of playing rugby with my friends, I picked flowers, was into cooking, I drew and painted. As a child I knew I wanted to be a painter, and that came from being a mermaid.

Did you have a role model, did someone inspire you?

My father painted when he was young. He was also a kind of tinkerer, he once built a popcorn machine and my mom started selling popcorn at the skating rink in Rabka Zdrój. He set up his pictures by that machine, so as he was selling the popcorn, he organized a miniature art fair. That was his little Rabka art fair. In his pictures he repainted postcards and other things he found with nice pictures.

Did you like your father’s paintings?

Yes, they were a major inspiration, it was really the only art I had access to as a child, apart from that there was only television and cartoons. Our home’s corridors and living room were full of those pictures—flowers, landscapes, sunsets. At first I tried to paint like Dad, later on I started doing my own things. I preferred painting to playing soccer, but I also had ways of inveigling myself into my friends’ circles. I drew their portraits, as thugs, for instance. Painting became my method of survival, I was hopeless at other things, but in art I shined. My parents didn’t quite believe in me at first, but eventually they began to be proud.

The mermaid metaphor is quite nice. I’m afraid it’s still relevant in Poland’s conservative reality.

You could say I’m still a mermaid in a pool full of piranhas.

Have you ever thought of leaving Poland, or of moving to another town?

Krakow has always been the best place for me to live. I was brought up in the countryside near Krakow, and in my house they used to say that living in Krakow was like being one step closer to God. That got lodged deep in my head and stayed there. Considering that I spend most of my time in the studio, however, I might as well live in London or in the Sahara.

Your pictures are filled with motifs. Where do you get your inspiration?

I can’t answer that. My inspirations are not so clear as some artists’, ones who have quite conceptual ideas for tackling a specific issue. I don’t work that way, my inspirations are a riddle even to myself. As I’ve said, as I work I revise my plans, something that started off as a cat might turn into an apple, and end up as a totally different object.

Are you trying to say that your creative process is more organic?

It happens more organically, it’s not planned. If I have a plan, it generally does not work out. It seems to me it’s tied to self-acceptance. For many years I rejected myself. I think I still have that problem and in fact I still don’t like myself; I’m fighting it, of course, but it comes from the society I grew up in. And now when I do something on the canvas I end up rejecting everything I invent. What stays is what I don’t do myself. The most appealing things are the ones that surprise me and which in fact aren’t my doing.

Krakow, August 15, 2022